|

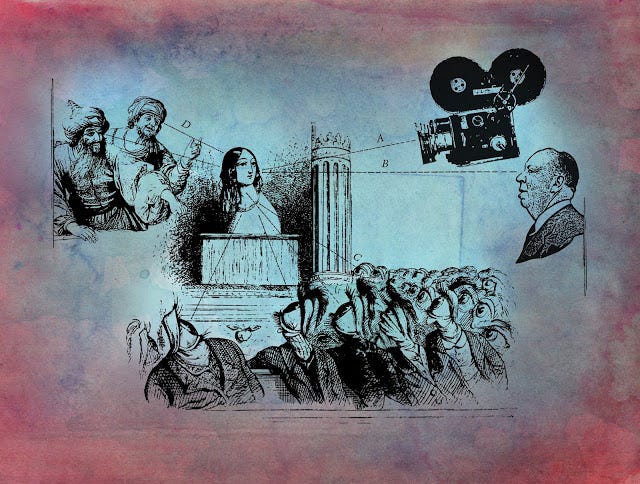

| Anatomy of the Gaze, yours truly, 2019 |

The background

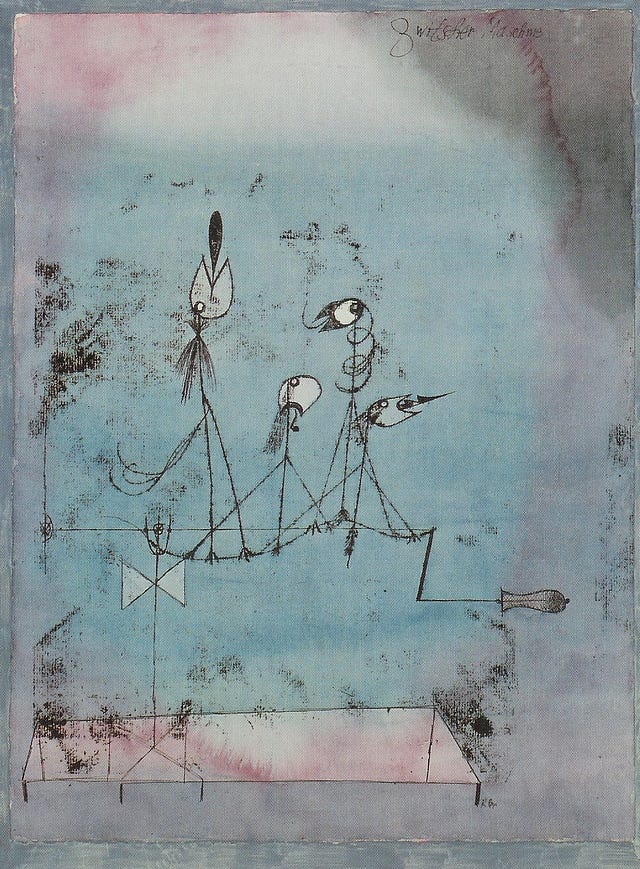

Maybe you’ve already noticed the resemblance between my picture and Paul Klee’s celebrated Twittering Machine (1922):

|

| Twittering Machine, Paul Klee, 1922 |

Klee was Hitch’s favorite artist, so I had to incorporate his work into my project somehow. I was attracted to Twittering Machine in particular because its apparent theme of man versus machine (or is it bird vis-á-vis machine?) relate organically to his technique in creating the piece: the original pen-and-ink drawing was imprinted on this watercolor-daubed paper surface via oil transfer, giving it a somewhat manufactured look. Thus the painting, like its subject, is a hybrid of human creation and mechanical reproduction. These thoughts weighed upon my mind as I used the digital tools in Adobe Photoshop to assemble and process the drawings, engravings and photographs that go into Anatomy of the Gaze. In the 1920s, in both his art and his lectures at the Bauhaus, Klee expressed ambivalence toward the relationship between nature and technology; Twittering Machine takes a wry look at the line that divides them and then smudges it. He would have giggled to know that Twittering reproductions would one day hang in the baby rooms around the world, insinuating joy and nightmares into countless newborns’ pre-lingual minds— but I don’t think he would have been surprised by the rise of Photoshop, Instagram filters and deepfake technologies that reduce the artistic struggle to that of a keystroke.**

Diagramming the gaze

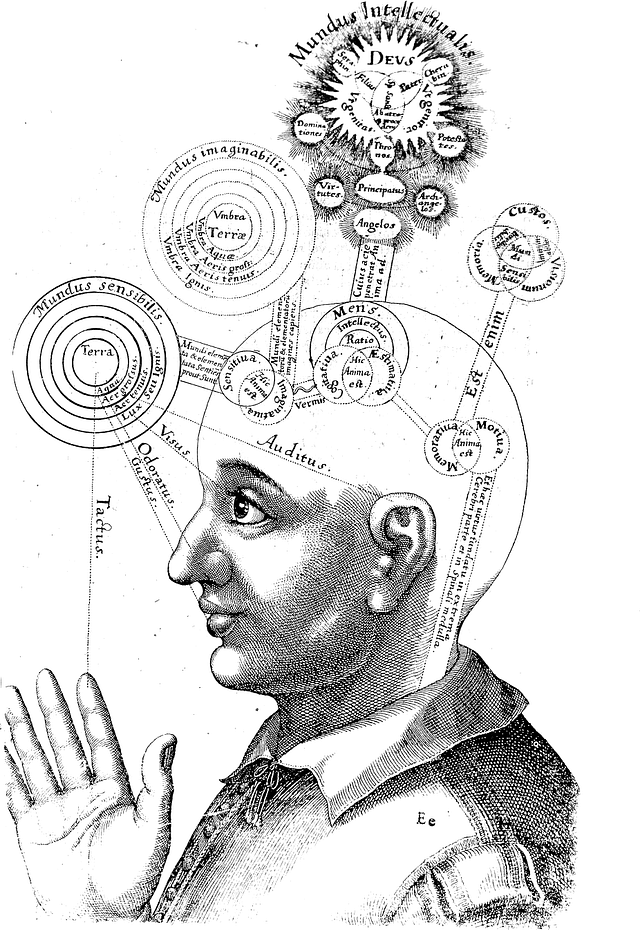

If Umberto Eco is my spirit animal, then Robert Fludd might be my…I don’t know… Wii avatar? His whackadoodle esoteric diagrams speak a truth to me that has nothing to do with science or maybe even reason; still, they compel me to, well, gaze upon them. His Representation of Consciousness (1619) has yet to be bested by modern science or philosophy, and what’s not to like about a guy who won’t shy away from explaining the unexplainable? His engravings reach across the centuries, inspiring me to create my Anatomy.

|

| Representation of Consciousness, Robert Fludd, 1619 |

The eyes have it—or—Jeepers, creepers, where did Dalí get those peepers?

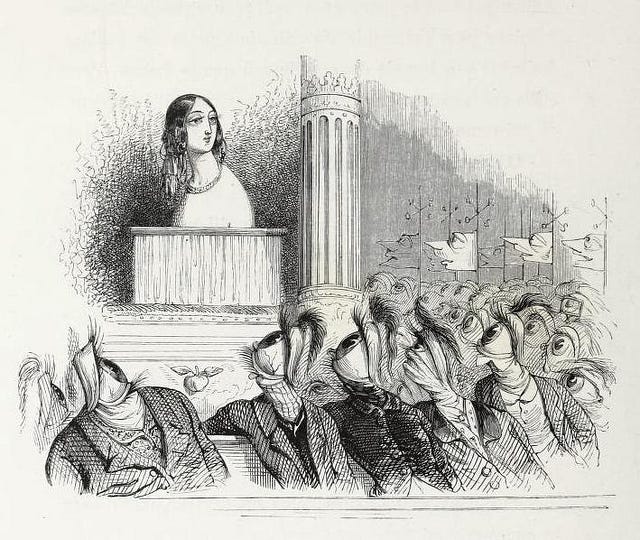

Hitch was a card-carrying surrealist, and through that (cough) lens, his films actually commented on feminist Gaze theory decades before it was articulated by Laura Mulvey. Think of all those scenes of his that weaponize the very act of looking, of watching, of voyeuring — even glances that break the fourth wall to set movie audiences on edge! When he hired Salvador Dalí to paint those bulbous, testicular eyes for Spellbound, it was a testament to his commitment to the Gaze. But even an original voice like Dalí had his influences—in this case, the 19th century French proto-Surrealist J. J. Grandville. For my infographic collage, I went back to the source to borrow the eyeball-dudes—not to mention the female objet d’attention—featured in Grandville’s It’s Venus in Person! Obviously, thinking artists have been considering the Gaze for quite some time.

|

| I’m pretty sure Dalí straight up stole the eye-guys from It’s Venus in Person!, (J. J. Grandville, 1844), but as of press time I haven’t been able to locate the picture. |

Uh oh, Susannah!

But what about those two guys in the upper left corner of my mishmashographic? Excerpted from Gerrit van Honthorst’s 17th century painting Susannah and the Elders, this touch is especially Hitchcockian. According to an apocryphal addition to the Old Testament Book of Daniel, the beautiful and virtuous Susannah spent so much time lolling in her backyard that the local gentry took up “watching eagerly, day after day, to see her.” One time, a couple of them spied her bathing naked and tried to coerce her into a threeway. She successfully fought them off, only for them to turn and frame her for adultery. So you’ve got some of Hitch’s favorite themes all wrapped up together: voyeurism, lust, violence. But here’s where it goes full Hitchcock: around the same time that van Honthorst was retouching Susannah’s nipples for the ocular delectation of future male gazers, Frans van Mieris the Elder (or possibly his son), was painting his own take on the story. (It seems every artist wanted a piece of her.) That version hangs in Norman Bates’ office parlor,*** and with deliciously metatextual panache, our murderous motelier hangs it over the peephole through which he spies on his victims! Naturally, I had to work that bit into the project.

So there you have it. My annotated little Photoshop project. If you’d like a signed, high-res print, ping me. I’m sure we can work something out.

*Basically, the idea is that, in cisgender western culture at least, men are predisposed to look at women, while women are predisposed to attract the look of men. As my digicollage illustrates, in classical Hollywood cinema, this gaze is compounded by the lens of (A) the camera and (B) the usually male director who concentrates its focus, followed by (D) the other male actors/characters who gaze upon her and finally (C) the gaze of the audience, for whose males such scenes are constructed. Back in the 1970s, British feminist film theorist Laura Mulvey expanded on this theme, with the aim of tearing down patriarchalism’s grip on Hollywood. Since then, she has tempered her views somewhat — or at least allowed for a variety of cinematic experiences outside of this heterosexual/patriarchal view. Meanwhile, mainstream Hollywood has responded by, at times, providing strong female protagonists who objectify and rescue their male counterparts. For example, ever responsive to the cultural zeitgeist, Disney creatives rewrote the Rapunzel story and empowered the princess to rescue herself and her beau in Tangled (2010).

**Though he might not have been surprised, I bet he would have barfed in his mouth at the delusions of artistic grandeur these technologies enable. For instance, while he sometimes distressed his works to give them an antique look, his motives were always future-facing and tempered by a pedagogical motives — never sentimental. Contrast that impulse with Instagram filters that enable amateur photographers to ejaculate nostalgia willy nilly onto the internet with the flick of a thumb. Oh! And while we’re on the subject of authenticity, in presenting this infographic, I’ll be the first to admit I’m not an artist. I’m just a movie geek having fun.

*** …but not in the Musée Hyacinthe Rigaud, from which it was stolen in 1972.

----------

----------

Comments