Screening Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo for first-time viewers makes me edgy. The stakes are personal: if my guests like the movie, I feel flattered, but if they don’t, I’m miffed. I don't think I'm alone in feeling this way. In fact, its intrinsic

merits aside, I believe this is why so much has been written about the film: Vertigo admirers often feel entitled—if not obligated—to put their two cents in.

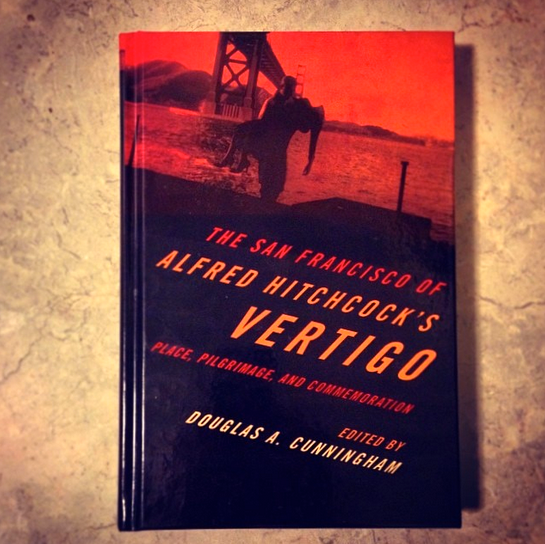

That’s the feeling I got reading the eclectic collection of

essays in “The San Francisco of Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo: Place, Pilgrimage and Commemoration,” edited by Douglas A.

Cunningham.

People might enjoy To Catch a Thief or North by Northwest for the Technicolor thrills, but when it comes Madeleine’s beautiful, phony trances at Podesta Baldocchi and points beyond, this time it’s personal, maybe even religious. In the book, Miguel Pendás recalls the time he spent as a tour guide driving Vertigo-philes around on their “pilgrimage to all the film’s locations” in the Bay area. Meanwhile, Cunningham writes about those sojourners’ rites as categorically different from the “casual ogling of curious film buffs; after all, the cinephilic pilgrimage [(there's that word again!)] is born of love (for the diegetic world of the film),” along with “loss (the apparent absence of that diegetic world within the realm of the real)” and a desire to briefly inhabit that world. 1

People might enjoy To Catch a Thief or North by Northwest for the Technicolor thrills, but when it comes Madeleine’s beautiful, phony trances at Podesta Baldocchi and points beyond, this time it’s personal, maybe even religious. In the book, Miguel Pendás recalls the time he spent as a tour guide driving Vertigo-philes around on their “pilgrimage to all the film’s locations” in the Bay area. Meanwhile, Cunningham writes about those sojourners’ rites as categorically different from the “casual ogling of curious film buffs; after all, the cinephilic pilgrimage [(there's that word again!)] is born of love (for the diegetic world of the film),” along with “loss (the apparent absence of that diegetic world within the realm of the real)” and a desire to briefly inhabit that world. 1

As with Jerusalem and Mecca (and Dyersville, Iowa), a cottage

industry has sprung up in the Bay area, geared

to help the faithful get the most the most from their visit. It’s astonishing

how close many of Hitchcock’s most famous movie locales are to each other: Shadow of a Doubt’s Santa Rosa and The Birds’ Bodega Bay are just an hour

or so away, while places all over the city itself provided the setting for

several other Hitchcock films. Contributors Jeff Kraft and Aaron Leventhal, who also wrote a

great companion to this book, note that there are frequent and “ongoing

events celebrating Hitchcock’s filmmaking in San Francisco.”

But if those other locations are holy sites, San

Francisco of Vertigo is the Dome of

the Rock. Want to see for yourself? You can even stay at Hotel Vertigo, formerly the movie’s Empire Hotel, and push your way into Judy’s old room—if

you’ve got some nerve. For my money, I’d rather blow a paycheck on a

room at the Fairmont, Hitch’s roadhouse of choice, where Scottie took Judy

dancing; be sure to get a room with a view of Madeleine’s Brocklebank

apartments across the street. Cunningham devotes five full chapters to the

consideration of what it means to take the Vertigo

city tour.

Hitch's Missionary Position

The book is at its most thought provoking when it turns its

attention to the film’s specific locales. Riffing on a fascinating history of

the California Mission Revival of the late 19th century, Martin

Kevorkian and Stanley Orr quote Phoebe S. Kropp’s observation that the movement

romanticized the less savory aspects of California’s Hispanic origins, smoothing out the facts of “conquest, genocide and war as well as race, class and

religious conflict.” The writers draw a direct line from such revisionism to

Hollywood’s incompetent Indians and pious Franciscan priests, such as those portrayed

in Douglas Fairbanks’ Zorro movies.

Leave it to Hitch to put the wrinkles back in the Revivalists’ story. Say the writers: “Through parodic allusion and quotation, Hitchcock

exposes the… California Mission Revival and its complicity with American empire

building.” Key scenes take place at Mission Dolores—California's oldest surviving mission—and Mission San Juan Bautista, whose tower was lost in a fire, but which Hitch restored using trick photography. The Mephistophelian industrialist Gavin Elster stands in for the

dark side of American Manifest Destiny, while the “ghost” of the scorned Carlotta

Valdez represents the Hispanics and Native Americans who footed the bill for

it. The authors quote Robert J. Corber, who notes, “In repeating Carlotta’s

story to Scottie and Midge, [bookseller Pop Liebel] indicates the importance of

recovering the history of Hispanics in the American West for constructing a

more accurate narrative of the nation’s past.”

Hitch’s own attitude on the topic manifests itself in the

movie’s first frames. The authors note that the opening chase is pursued across

clay-tiled mission-style rooftops, and that the script called for an “Italian

type, with rough features.” In other words, the movie opens on the image of an

immigrant, minority “other” running for his life. From the start, Scottie’s

(and, therefore, our) place in and grasp on history are shown to be literally flimsy.

In a field where so many ideas get regurgitated ad nauseum,

it’s refreshing to read original writing on Hitchcockian topics! This chapter

alone makes the book worth the purchase price, highlighting Vertigo as a key antecedent to the

intimations of Native American genocidal guilt that seep through in The Shining and Poltergeist and of the profligacy of American imperialism hinted at in Eyes Wide Shut.

From Vertigo's opening, Hitch disrupts his audience's expectations: the opening title sequence starts out in black and white—a motif that's also played out in scenes inside staircases and the bell tower.

A Dark VistaVision

Hitchcock dedicated prodigious thought to every aspect of

his films’ production. He even thought long and hard about his film stock

choices and how they might relate to the themes his stories explored. For

instance, when called upon to shoot a film in 3-D—Dial M for Murder—he chose to adapt a stageplay, using that faddish technology to privilege the audience to join the actors onstage. Psycho, a film about the use (and

misuse) of eyes, was shot with a 50 mm lens on 35 mm film stock—all the better

to implicate the audience in that story’s voyeurism by replicating the natural

field of human vision. Vertigo, however, was

shot in VistaVision. How does that relate to the story?

Contributor Ana Salzburg offers a few interesting ideas. In the

1950s, studios experimented with a variety of big screen formats, such as

Cinemascope and Cinerama. While they emphasized horizontal

width, Paramount’s VistaVision allowed for a taller field of view as well. Further, shooting (not just

projecting) in VistaVision allowed for greater depth of field—an important attribute, I’d add, in a film whose special effects were designed to bring the dizzying sensation of acrophobia to the screen.

Salzburg meditates on how Hitch may have used the unique

attributes of VistaVision as a storytelling device, suggesting that he exploited

the technology’s capability to express vertiginousness. While at Mission

Delores, Scottie is framed in a low angle medium shot, with the church tower

looming overhead, “expressing kindred verticality between Scottie and the

mission”—a shot made all the more powerful (if not also possible) by VistaVision. (Click images to enlarge.)

In one of the most sublime and haunting scenes in the film,

Scottie and Madeleine are dwarfed by the monumental sequoias at Big Basin

Redwoods State Park. “Majestic in their extreme verticality, massive in their

breadth, the redwood trees seem to encompass coordinates parallel to those of

the VistaVision screen itself.”

The scene at Fort Point combines a full view of the bridge, the bay and Madeleine’s haunted, diminished

figure. Likely, such framing couldn’t have been accomplished without VistaVision. This

scene is one of the most iconic in all cinema, and the grandeur afforded by VistaVision helped make it so.

Stacks of articles have been written about Vertigo, along

with several books, leading with Dan Auiler’s “Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic.” At 334 pages and

containing the contributions of 17 authors, “The San Francisco of Hitchcock’s Vertigo” takes its place among them. It

offers a sweeping, yet idiosyncratic (in the best sense of the term) view of

one of cinema’s most treasured jewels, in one of the world’s most-loved cities. Having helped preserve its memory, some of these writers, like Scottie, might feel responsible for it now. Whatever the case, this book is clearly a personal labor on the part of its contributors and its

editor—an apt response to one of Hitch’s most personal works. Only a film as

beguiling and beautiful as Vertigo

could inspire such a project.

------------

While Cunningham makes a good point, I don't think other film fans should be so quickly dismissed. What about those who fly all the way to Iowa to see the “Ghost Players” emerge onto its Field of Dreams for one more pickup game? Something special is going on there, too. Definitely, more could be written about “cinetourism.” As Phoebe S. Kropp wrote elsewhere: "

------------

While Cunningham makes a good point, I don't think other film fans should be so quickly dismissed. What about those who fly all the way to Iowa to see the “Ghost Players” emerge onto its Field of Dreams for one more pickup game? Something special is going on there, too. Definitely, more could be written about “cinetourism.” As Phoebe S. Kropp wrote elsewhere: "

Comments

Thank you!

My best,

Martín Sichetti

Check this link:

http://martinsichetti.com/